Celadon From Mengrai Kilns

|

| |

| |

"Celadon"

is the commonly accepted name for kind of high-fired

stoneware with a wood ash glaze (usually crackled), which is

hand crafted by a traditional process believed to have been first

developed in China some 2,000 years ago. In Chiang Mai, the

glaze is usually made of silt from a rice field and wood ash

from a particular tree. The body of the pot is made of stoneware

clay (know as "din dam", literally black earth)

froma local deposit. When fired in a reduction atmosphere (high

Co2, low o2 content), the natural iron content of the glaze and

of the body combine to produce the delicate shade of green which

is associated with gook celadons. Too much oxygen in the kiln

gives different shades, varying from olive green through yellow

to brown. The glaze can be varied by using other kinds of ash

(i.e. rice stalk, bean stalk, or bamboo), and other clays.

In the

final firing, the kiln must be taken to about 1,260C in order

to vitrify the glaze. The result is a bright transparent gloss

finish. The crackle (otherwise known as 'crazing') is caused by

a difference in the coefficient of contraction between the body

and the glaze when the pot is cooling. |

|

|

Why is it called "celadon"?

One theory is

propounded

by William Willetts in "Chinese Celadons and

Other Related Wares in Southeast Asia" (South-east Asian

Ceramics Society, Singapore, published by Arts Orientals,

Singapore, 1979). He writes: "There is moreover no reason to

suppose that the ware was known as celadon until the last years

of the 19th century…..(when)…the word 'celadon' was used to name

a colour,… of a costume worn by the shepherd Celadon in….the

17th-century pastoral romance L'Astree, by Honore d'Urfe… Not

until the 6th…edition of the Concise Oxford

Dictionary (1976) do definitions relating to ceramic

materials appear…namely (1) 'grey-green glaze used on some

pottery' and (2) 'Chinese pottery thus glazed'. "Willetts comments

that the Complete oxford English Dictionary (a much bigger work)

did not define celadon correctly until 1945- if I understand him

well - when it indicated that celadon denoted the "high fired

stoneware made at the Lung -ch'uan kilns in Chekiang province of

eastern China from Suang times onwards and, at various times

subsequently, at other factories in other parts of country and

abroad".

Turing

back to the publication by the Southeast Asian Ceramics

Society referred to above, we find an article

by Lu Yaw. He attacks the term 'celadon' as an

historical misnomer, and prefers the name "qing ci"

, meaning green or bluish-green porcelain ware,

(Romanized Japanese "seiji"). He then goes on to note that the

Ashmolean Museum of oriental Art (Oxford) and the Museum

Pusat (Jakarta) have discarded the term 'celadons, and

use "Chinese green wares" instead. He adds that the

Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art (London)

may be moving in the same direction. But he then tends to

destroy his own argument by saying that, in certain firing

conditions, these 'greenwares" may not be green at all, and may

even be 'yellowish or brownish". |

Here we would add that some green

coloured wares,

for example those with a lead based copper glaze fired in

oxidation, can certainly not be regarded as celadons. And

finally, a practicing potter calls a "green pot"

one which has been thrown and air dried, but not yet bisque

fired.Consequently, we prefer to agree with Willetts. He does

indeed ask why one should use a word of European derivation

(celadon) "to name the product of a Far Eastern potter when the

Chinese term 'ch'ing tz'u' is lying at hand”. He answers his own

question by saying that celadon' conjures up and image of this

class of proto-porcelain in all its beauty, whereas the other

term.

does not. He speaks

as a Westerner and we are Asians. All the same, we prefer'

celadon. Everybody the world over who likes pots clearly

understands what that means, and has an instant concept of this

unique art form Anyway, what's in a name? Let us enjoy the visual

and tactile pleasure pleasure of these unique pieces, and be

grateful to the old potters long dead who taught us how to make

them for our delight, and that of generations still unborn.

How long will the craft persist in

its present

form? I hesitate to guess. But I fear that before long one will

not be able to find the raw materials needed for making celadons

in the traditional way. And what of the essential loving skill of

the artist craftsmen who so proudly sing each

Mengrai pot they make to day? We can pass on

our craft to our children: but cannot be sure that it will be

there for our grandchildren to inherit. Perhaps this thought puts

the value of Mengrai hand crafted wares in better perspective.

|

|

A brief celadon

and stoneware production

process |

2.1 The

dried stoneware clay is reduced to powder and sieved. It is then

mixed with water, passed through a pug mill to improve the

blending, and allowed to age for a while by bacteriological

action.

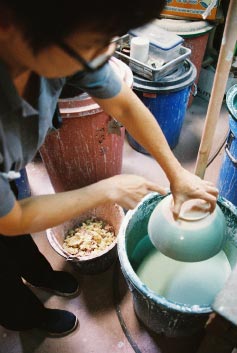

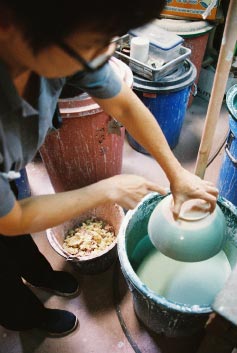

2.2 Before throwing on the wheel,

the

clay is kneaded, to remove air bubbles and to improve plasticity.

2.3 After throwing, the pots are

allowed to

dry until they are "leather hard". They are then often hand

carved, incised of embellished with a high relief applied

decoration. Thereafter, they are allowed to dry naturally in the

air. When quite dry, they are checked for cracks and defects.

2.4 At this point, the pots are still

"green”. That is, they will revert to mud if put into a bucket of

water

2.5 The next step is bisque firing,

in a

tub kiln, to about 800 C. Though stable in water, the bisque ware

pots are still porous. A second check for cracks and defects is

made

2.6 The bisque pots are then

glazed, usually by

dipping in the glaze mix, and allowed to dry.

2.7 The final firing follows, to

1,260 C or

1,300 C in a reduction atmosphere, as already described. The pots

are again checked for defects, cracks or leaks. From start to

finish, the process takes about one and a half months. |

|

|